Mark Stanway.

Keynote Speaker. Freelance Site Manager

YouTube Onward Shift Mark Stanway

BUILDING THE FUTURE BY LEARNING FROM THE PAST. A CO-OPERATIVE TRADES MODEL FOR HOUSING.

What about trying a different model?

One rooted in community, sustainability, and the transfer of skills, where local tradespeople build homes for their own communities, employed directly by housing associations.

It’s a concept that borrows the best of the past and reshapes it for today’s challenges.

Before the 1980s, many councils employed their own construction teams through Direct Labour Organisations (DLOs).

Skilled tradespeople, bricklayers, joiners, plumbers, roofers all worked on secure, long-term contracts to build and maintain housing stock.

These teams trained apprentices, offered local employment, and delivered high-quality homes without the profit margins of private firms.

The system wasn’t perfect, but it gave communities homes built with pride and public purpose.

This new concept proposes reviving that model through worker cooperatives.

Instead of relying on subcontractors or national developers, housing associations could partner with democratically run groups of local tradespeople.

These cooperatives would not only build homes but mentor young apprentices, ensuring vital skills are passed on.

It's a way to regenerate communities while tackling the housing crisis and the widening skills gap in construction.

However, the model isn’t without its challenges.

Governance can be complex, balancing democratic decision-making with the need for efficient project management.

This could be addressed by electing cooperative boards for strategic decisions while leaving day-to-day operations to experienced site managers.

Funding is another hurdle.

New cooperatives may lack the financial track record to secure loans or materials.

Here, housing associations and social investors could step in with upfront capital and phased payment structures, supported by grants for training and innovation.

Meeting housing association procurement standards can also be a barrier.

Working closely with partners to develop frameworks for pilot projects, especially in regions with high need and available trades, can create a path forward.

Cultural change may be needed, too.

Some tradespeople used to subcontracting might hesitate to join a cooperative.

Offering a mix of salaried and flexible roles could make the model more appealing while ensuring stability.

Despite these hurdles, the potential rewards are significant.

Homes built to higher standards, local jobs, meaningful apprenticeships, and wealth retained in the community.

This model fosters pride, ownership, and a sense of shared purpose.

With vision, support, and strong partnerships, this isn’t just a nostalgic idea, it could be the foundation for a fairer, more resilient future in housing.

Its easy to constantly criticise the current system, but rather that criticise, come up with solutions.

Add positivity, hope, a way forwards.

My idea may be pie in the sky, but it’s a start.

MENTAL HEALTH, IS IT TIME TO RETHINK OUR PRIORITIES?

When I began my Carpentry and Joinery apprenticeship in 1979, it was with a small, family run business where many of the tradespeople had worked there for years.

While safety standards weren’t always a priority, there was a strong sense of camaraderie, and life felt stable and predictable.

At home, we didn’t have central heating or double glazing, and winters meant waking up to ice on the inside of the windows.

Life was simpler, and despite hardships, there was a greater sense of security and community.

Today, however, society operates on a profit driven model that prioritises financial gain over wellbeing of individuals.

This shift had a profound negative effect on mental health, living standards, and social cohesion.

The relentless pursuit of profit has deepened inequality and fostered an environment where human connection and care often take a backseat to economic growth.

One of the most serious consequences of this model is the worsening mental health crisis.

Work is now valued above personal time, leading to widespread burnout, stress, and anxiety.

Many people are pushed to work longer hours, some in precarious employment, some with little concern for their wellbeing.

The pressure to be constantly productive and generate higher profits leaves workers feeling inadequate and exhausted.

Mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders are becoming more prevalent as individuals struggle to balance work with personal life. Beyond mental health, living standards have also declined for many.

Wages have stagnated while the cost of living, especially in urban areas, continues to rise.

Essential services like housing, healthcare, and education are increasingly privatised and commodified, making them inaccessible to large segments of the population.

Job security is diminishing, with zero-hour contracts and outsourcing, becoming the norm, further contributing to financial and emotional instability.

Is it time to rethink our priorities?

A return to stable, direct employment would not only restore job security, but also trust, community and dignity in the workforce.

We must reject a system that treats workers as disposable and instead demand a model that values people over profit.

A future where individuals have secure jobs, fair wages, and a healthy work life balance is not just idealistic, it is necessary for a functioning, compassionate society.

If we fail to act, the mental health crisis will deepen, inequality will widen, and generations to come will suffer the consequences.

The choice is ours, continue down this destructive path, or fight for a future where security, wellbeing, and human dignity take precedence.

THE DAY A LOOSE BATTERY ALMOST SHATTERED THE PAST

About 20 years ago, I was hired by a roofing company for a unique and delicate task, protecting priceless pottery artifacts at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.

Since these artifacts were too large to move, the museum was concerned that debris from the flat roof renovation might fall and damage irreplaceable pieces.

My job involved constructing wooden enclosures around the pottery.

I carefully cut plywood and attached it to a timber framework, securing everything with screws.

On my third day, I was working on encasing a large Victorian vase when something unexpected happened.

As I was screwing a piece of plywood into place, the battery from my cordless screwdriver suddenly detached and fell.

My heart sank as I watched it drop in slow motion.

It narrowly missed the bottom of the vase before hitting the floor.

From that moment on, I made sure to tape the battery to the screwdriver for extra security.

In all my years of using a cordless screwdriver, nothing like that had ever happened before or since.

The timing of the incident was almost unbelievable, and it made me realise how even the smallest, most routine hazard can turn into a potential disaster under the right circumstances.

This experience was a powerful reminder of the importance of checking tools before use.

We often take for granted that they will function as expected, but even minor malfunction at the wrong moment can have serious consequences.

Regular maintenance and double-checking equipment can prevent accidents, especially in situations where stakes are high.

THE CHANGING FACE OF THE UK CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY.

In the U.K. in the 1970’s, the construction industry was dominated by small, family run businesses.

These companies typically had a stable workforce, where tradespeople enjoyed long term job security and were valued for their skills.

Employers took pride in their teams, fostering loyalty and high standards of workmanship.

Many workers stayed with the same company for their entire careers, creating a sense of stability and trust between employees and employers.

However, in recent decades, the industry has undergone significant change, influenced by global economic shifts and the adoption of the corporate business models.

Large construction firms have increasingly taken over, prioritising rapid growth and profitability.

Many of these companies seek investment or aim to float on the stock market, where short term gains often take precedence over long term stability.

One of the biggest changes has been the rise of subcontracting.

In the past, construction firms employed their own tradespeople, ensuring consistency in quality and standards.

Today, most of the work is outsourced to subcontractors, leading to a fragmented workforce with less job security.

Workers are now often treated as temporary resources rather than valued team members.

The system has reduced accountability, as companies focus more on cutting costs than maintaining high quality workmanship.

The shift towards a profit driven model has also led to financial instability within the sector.

Many firms take on large contracts with tight margins, leaving them vulnerable to economic downturns or unexpected costs.

This has resulted in a cycle where companies grow rapidly but struggle to sustain themselves, leading to frequent bankruptcies.

In turn, this affects workers, who are often left without pay or job security when firms collapse.

While the construction industry remains a vital part of the U.K economy, the move away from traditional business models has raised concerns about declining standards, worker welfare, and long-term sustainability of the sector.

Whilst safety standards have improved over the decades, there is a significant rise in poor mental health in the construction industry today, perhaps this is the reason why.

Unless a balance is found between profitability and quality, the industry may continue to face challenges that undermine its future stability.

TRADESPEOPLE OFTEN FIND WAYS TO COMPLETE THEIR WORK

Tradespeople often find ways to complete their work, sometimes at the expense of safety, both their own and others’.

Rather than refusing to proceed until conditions are safe, they may push forward despite the risks.

This tendency is often driven by financial incentives, but there’s more to it than that.

Many tradespeople become deeply engrossed in their craft, focusing entirely on their work without consciously considering safety.

Much like an artist absorbed in their creation, they may not naturally think about potential hazards.

When they first learned their trade, the emphasis was likely on mastering tools and techniques rather than prioritising safety.

As a result, health and safety protocols may not come instinctively to them.

Their actions are not deliberately unsafe, rather, they reflect the way they were trained.

This is why workplace safety education must go beyond standard guidelines and regulations.

Real life experiences from individuals who have suffered life altering accidents can be a powerful tool for raising awareness.

Hearing first-hand accounts of how things went wrong can provide valuable insight, helping workers understand the real consequences of neglecting safety measures.

By learning from these experiences, tradespeople can begin to recognise and address risks before they lead to harm.

HUG

After 29 years of marriage and countless embraces, my wife’s first instinct when I returned home after a week in hospital was to hug me.

But I couldn’t.

My body was in too much pain, and it would stay that way for over a year before she could finally hold me again.

The physical closeness we had shared for nearly three decades was suddenly taken away, all because of a workplace accident.

Something as simple as a hug, something we had never thought twice about, was now impossible.

The pain wasn’t just mine, it was hers too.

She had to watch me suffer, unable to offer the comfort of her touch.

People often think of workplace safety as just another rule, another regulation.

But when an accident happens, it changes everything.

It doesn’t just impact the person who gets hurt, it affects their loved ones, their daily lives, and even the simplest moments they once took for granted.

For over a year, my wife had to hold back the one thing that came naturally to her, offering love and reassurance through a hug.

The ripple effect of that one accident was more than just physical pain, it was emotional, mental, and deeply personal.

Workplace safety matters.

It’s not just about avoiding injury, it’s about protecting the moments that make life meaningful.

Don’t take it lightly, because when something happens, it’s not just you who suffers, it’s everyone who loves you.

REWARDING PROJECT

One of the most rewarding projects I ever worked on as a joiner was building my own house.

Although I was a joinery contractor, employing other joiners and working on many fascinating projects, this one was different.

It wasn’t about profit or meeting deadlines for a client, it was about bringing my own vision to life and creating a home for my family.

The only financial concern was ensuring I had enough resources to make my creative ideas a reality.

In the trade, it’s easy to lose the joy of craftmanship as work becomes solely about productivity and efficiency.

The pressure to meet targets can strip away satisfaction that comes from building something with skill and care.

Even more concerning is when productivity is prioritised over safety, leading to life altering or even fatal consequences.

In today’s world, workers are often treated as commodities, valued only for the profit they generate for a company.

No matter how much effort we put into our work, if an accident happens and we can no longer contribute to the bottom line, we are too often discarded without a second thought.

The true worth of a craftsperson should not be measured solely by output and profit, but by the skill, dedication, and passion they bring to their work.

A FAIRER APPROACH TO BUILDING SAFETY COSTS

The UK’s Building Safety Levy, set to be introduced in 2025, aims to fund the remediation of unsafe buildings.

However, by placing most of the financial burden on property developers, it risks increasing house prices as developers pass on costs to buyers.

A fairer approach would be to distribute responsibility across all parties involved in past building safety failures, not just developers.

A more balanced solution could involve a Building Safety Remediation Fund, with contributions from:

Developers, based on project size and past involvement in unsafe buildings.

Manufacturers that supplied defective cladding and insulation.

Insurers & Warranty Providers, who profited from covering unsafe buildings but often refused pay-outs.

Government, since outdated regulations allowed unsafe materials to be used.

Additionally, the government could introduce a manufacturer levy, specifically taxing companies that produced and sold materials that contributed to fire risks.

This would ensure those who profited from unsafe products contribute to fixing the problem.

Rather than a flat levy that could slow down construction, the government could provide low-interest remediation loans to developers, allowing them to spread costs over time.

This would prevent immediate price hikes on new homes and ensure developers can continue building.

For long-term protection, the UK could introduce a National Building Safety Insurance Scheme, where all construction firms pay into a central fund.

This would create a continuous funding source for future remediation, like employer liability insurance.

By spreading the financial responsibility more fairly, this approach would protect homebuyers, maintain housing affordability, and hold all responsible parties accountable.

The government should reconsider whether targeting developers alone is the right solution, or if a shared responsibility model would lead to better outcomes for both the housing market and public safety.

WHILST TRAVELLING TO A MEETING LAST WEEK

Whilst travelling to a meeting last week, covering around 70 miles, I noticed several construction activities, many involving unsafe working practices.

One site had four construction workers extending a live commercial building.

However, they were working without proper scaffolding, creating a serious fall risk.

Further along, I saw three bricklayers on trestles extended to their maximum height, rebuilding a gate pillar at a luxury property.

This was another clear fall hazard.

Although this was a domestic project, the property owner was a businessman with multiple large car showrooms, meaning he likely understood health and safety regulations.

Yet, no precautions were being taken.

Later in the journey, I observed two workers standing on ladders, placed on a flat roof whilst fitting a barge board to the gable end of a domestic building. Again, there was a significant risk of falling.

Falls from height remain one of the leading causes of reportable workplace accidents under RIDDOR in the UK.

The Construction design and management Regulations (CDM) imposes duties to prevent such risks, yet none of these workers seemed to be following them.

This highlights a critical issue in the industry, compliance alone isn’t enough.

We need a cultural shift where workers want to work safely.

The real challenge is education, getting workers to recognise the personal impact of unsafe practices.

Training must go beyond simply following rules.

It should emphasise real-life consequences, using case studies and testimonies from those who have suffered workplace accidents.

Workers must understand that an accident can mean loss of income, permanent disability, or even death, affecting not just themselves but their families.

Financially, it can lead to medical expenses, loss of earnings and potential legal action.

Emotionally, it can devastate loved ones, causing stress, anxiety, and long-term hardship.

Employers, industry leaders, and training providers must make safety training more engaging and relatable.

It needs to be ingrained in the industry culture, reinforcing that choosing to work safely isn’t just about following regulations, it’s about protecting their future and the well-being of those who depend on them.

Until workers truly understand these risks, unsafe practices will continue.

The key is shifting the mindset from having to work safely to wanting to work safely.

I deliver an engaging, real-life talk on how daily site hazards are created through actions and inactions and empower your workforce to improve safety awareness and practices.

My talk takes from forty to sixty minutes, with questions and answers afterwards.

This can be delivered in person or online.

HEALTH AND SAFETY CHALLENGES

I recently gave a talk on Health and Safety in Central London.

Whilst there, I realised that I hadn’t been in the city since 2012, when my company erected a timber kit for the (then) new Travelodge in Vauxhall.

It was a high-profile project due to its proximity to Vauxhall train station and the MI6 building, leading to frequent HSE inspections.

This project was particularly challenging, because there was no on-site storage.

Panels had to be directly lifted on to the level to be erected as soon as the delivery vehicles arrived.

There was a two-day window for the panels to be erected, then a day for pods, followed by the floor cassettes delivered the following day, and put in place, ready for panels the next day.

The panels were supplied by a large timber frame company which was situated two hundred and seventy miles away.

The floor cassettes supplied by the same company, had been subcontracted out to a small manufacturer in Manchester.

Because of the long transportation distances, I had to give two days notice to stop a delivery.

Unfortunately, the floor cassette manufacturer struggled to meet the requirements.

They frequently delivered cassettes in the wrong order and for the incorrect levels, causing major disruption on site.

Despite the challenges, my company pushed through, though the situation made health and safety especially difficult, particularly regarding edge protection.

This experience reinforced the importance of manufacturers selecting reliable suppliers.

A lack of performance doesn’t just cause delays, it creates serious safety hazards on site.

NOBODY SHOULD BE MADE TO FEEL WORTHLESS.

Lying on the ground after falling approximately 10 meters, I was badly injured, yet the site supervisor’s first instinct was not to check on me, but to cover his tracks.

Rather than ensuring my safety, he secured the ladders to the scaffold to hide the fact that he had neglected his pre-start checks.

I was broken, but to him, I was an inconvenience.

Hours later, my wife received a call.

The contracts manager, who wasn't even in the country , downplayed my accident.

He brushed it off with a flippant remark: “You know what he’s like, swinging around the scaffold.” As if I had done this to myself.

As if my pain, my suffering, was just an afterthought in his desperate attempt to shift blame.

The company wasted no time altering documents before the HSE could arrive, twisting reality to distance themselves from responsibility.

Then came the hospital, where doctors initially planned to reconstruct my rib cage to save me from a lifetime of agony, only to suddenly change their minds.

A few days later, they sent me home, to be driven 200 miles in my own truck.

I felt every bump in the road on the journey back, the pain excruciating as my flail chest bones dug into surrounding tissue.

My body shattered, my pain barely managed, no follow-up appointment.

Was I just being sent home to die?

Months later, when I hoped for some recognition, some understanding of the errors the company had made, their health and safety company brushed my suffering aside, an inconvenience to the company, who were trying to pretend it never happened.

Their indifference crushed me.

I spiralled into a darkness I wouldn’t wish on anyone.

Nobody should be treated like this.

Nobody should be made to feel worthless.

Mistakes happen, but covering them up only deepens the harm, making the insufferable emotional pain unbearable, at a time when someone is at their most vulnerable.

We must do better, be honest, be accountable, and most of all, treat people with the dignity they deserve.

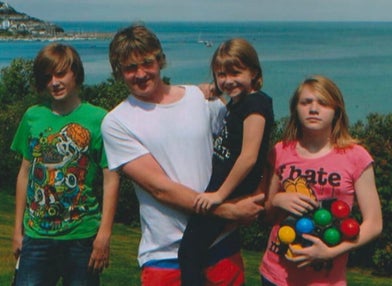

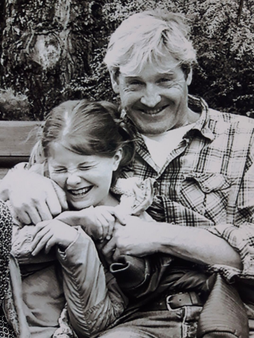

DAD

After my life changing accident at work, when I fell approximately 10 metres, sustaining multiple injuries including trauma to my head, I suffered emotional dissociation.

“The Children called me Dad.”

The words hung in the air, familiar yet distant.

I looked at them, confused.

It had been a couple of months since my workplace accident that changed everything.

But I wasn’t Dad.

My dad was Dad.

I was his son.

So why were these children looking at me with love, expectation, and a history I couldn’t remember?

I knew, logically, they were mine.

I had raised them for over 20 years.

I had tucked them into bed, cheered at their school plays, wiped their tears.

But now, I felt nothing.

No warmth, no connection, just a hollow detachment I couldn’t explain.

I tried.

For years I tried.

I searched my mind for memories that wouldn’t come, for emotions that felt just out of reach.

How do you be a dad when you don’t feel like one?

I thought of my own father, his strength, the way he carried the weight of fatherhood without hesitation.

Was that how you did it?

Was that enough?

But what about the children?

How did it feel for them to have a father who had forgotten to love them?

The thought crushes me every day.

The guilt is suffocating.

I robbed them of something fundamental, something they deserved., the unconditional love of their father.

A few days ago, my wife mentioned an article that said, parents should apologise if their children later say they were hurt by how they were raised.

But should we?

My accident wasn’t intentional, yet it shaped how I connect.

Behind every scar is a story, yet blame comes too easily.

We raise our children the best we can, despite life’s battles.

The world demands apologies for wounds we never meant to inflict, but what about the pain we carried?

Are we failures for not being perfect, or simply human, doing our best with what we had?

I don’t know if I’ll ever fully be the father I once was.

But I do know this, I will never stop trying.

Maybe that’s what being a dad really means, being a parent really means.

An accident in the workplace scars many, the ripple effects are far reaching.

There is a current trend today about what you would tell your younger self if you met for a coffee.

I would tell my younger self on the morning of my accident, “go back to bed.”

IS IT TIME THAT SECTION 2 PARAGRAPH 18 OF RIDDOR ADDED FURTHER REQUIREMENTS?

ACT BEFORE THE INCIDENT, NOT AFTERWARDS.

A recent incident involving a frustrated scaffolding contractor, highlights a growing safety concern on construction sites.

Upon arrival to install the next lift of scaffold, the contractor found the existing scaffolding compromised, the loading bays overloaded, bricks loaded where they shouldn’t be, ladder access altered, and crucial safety features like toe boards and brick guards removed.

Each of these reckless modifications posed a significant risk of injury or even death.

While the issues were rectified before work continued, this raises a crucial question.

Should scaffold access be removed and sites shut down when such dangerous tampering occurs?

If site management allows this behaviour, what’s to stop it happening again on the next lift?

More importantly, if a serious accident were to occur after previous warnings, could the scaffolder be held liable despite identifying the risk earlier?

Current safety regulations under RIDDOR (reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations) focus on incidents after they occur.

However, amending section 2, Paragraph 18 to include potential hazards, such as scaffold tampering or overloading, could prevent disasters before they happen.

If enforcement authorities issued fines and HSE costs for unsafe modifications, site managers might take these issues more seriously, discouraging reckless behaviour.

Scaffolding is a vital yet vulnerable structure, and its safety relies on strict adherence to regulations.

Without stronger deterrents, the industry risks preventable tragedies.

Perhaps it’s time for a regulatory shift, because waiting for an accident is no longer an option.

NEVER TAKE ANYTHING FOR GRANTED

When running my own carpentry and Joinery contracting business, one of the services I provided was timber frame kit erections.

I frequently worked with a major UK timber frame manufacturer, who would supply the cranes for lifting, but in return I was responsible for creating the lift plan for the projects.

They would propose the position and size of the crane that they wanted to use, which was generally governed by the cost of the crane hire.

One particular project involved erecting timber frames for a block of nine terraced houses on a brownfield site.

The fronts of the houses were about a metre back from the pavement and had a rear garden area of around seven metres depth.

Access to the rear of the properties was limited to a six-metre-wide strip at the end of the block of nine terraced houses.

The timber frame company proposed positioning a crane in the rear garden area and asked me to provide a lift plan showing this using a 40-tonne crane.

I visited the site to inspect the area and meet the contracts manager for the project.

Upon examining the rear gardens, I noticed a hedge at the bottom of the gardens but couldn’t access this area as it was behind the Heras fencing.

I asked the contracts manager what was behind the hedge, and he replied that he did not know.

This prompted me to investigate further, and I discovered that behind the hedge was the top of a wall, with a drop of around 2.4mts.

At the bottom of the wall was a footpath that ran alongside the canal.

Clearly the garden was not suitable to place a crane with the height difference in the ground, which the contractor should have highlighted to the timber frame company in the initial inquiry.

This incident highlighted the importance of thoroughly surveying the work area before proceeding with any lifting operations.

I had to position the crane at the end of the block of terraced houses, and due to the reach, I needed a much larger crane, which was considerably more costly.

It’s vital to identify all potential hazards and put control measures in place to ensure safety on site.

A detailed site survey can prevent costly errors, avoid project delays, and ensure the safety of workers and equipment.

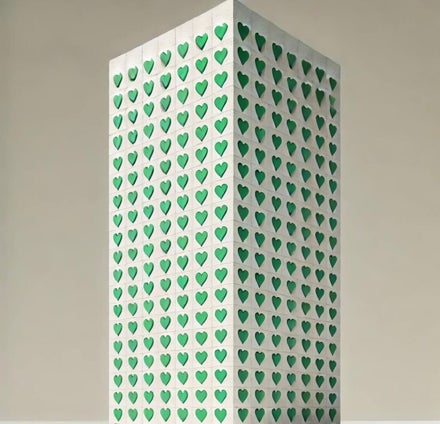

GRENFELL TOWER, A MONUMENT OF REMEMBRANCE, NOT ERASURE.

The government’s decision to demolish Grenfell Tower and replace it with a memorial raises difficult questions about accountability, remembrance, and the value of human lives in urban spaces.

The tower was originally clad to make it more visually appealing to wealthier residents, a tragic irony given the cladding itself was the catalyst for the fire that engulfed the building, killing 72 people.

Now, with the planned demolition, it seems history is being tidied away, erased rather than confronted.

If Grenfell is to be replaced, it should not be a subtle, sanitised memorial that fades into the cityscape.

Instead, it should be a powerful statement, an unmistakable presence in the skyline.

A structure as tall as the original tower, wrapped in solid, fireproof white cladding, standing as a stark reminder of the lives lost and the systemic failure that led to their deaths.

Seventy-two green hearts should be embedded in the precise locations where residents perished, making their loss visible to the world.

This should not be a passive memorial, but a beacon, an unavoidable, towering testament to injustice.

It must serve as a constant challenge to those in power, a demand for change, and a symbol of resilience for the survivors and families left behind.

Anything less risks making Grenfell just another forgotten tragedy, swept aside for the comfort of the privileged.

NEVER GIVE UP.

In 2000, I completed building my own house in just under four months.

However, this personal milestone left me financially drained, I couldn’t even afford bathroom blinds, much to my wife’s frustration.

At the time, I was competing for a lucrative Carpentry and Joinery contract for 120 houses in the West Midlands.

The quantity surveyor assured me the contract was mine if I reduced my price by 1.5%.

Desperately needing the job, I agreed, stipulating that unforeseen costs would be charged as additional expenses.

I submitted a front-loaded breakdown, ensuring the initial phases of work received substantial payment.

For several months, the project progressed smoothly, but discrepancies began emerging.

Site materials and plans did not align with specifications, resulting in legitimate variation claims.

Initially, these were honoured, but over time, the company began underpaying my applications.

When challenged, the quantity surveyor dismissed my variation claims, labelling them part of the original contract.

By then, I was also carrying out the carpentry works on a care home for the same company, who were having issues with the Clerk of Works, who was a stickler for detail.

Most of the contractors were ignoring the Clerk of Works requests at their peril, whereas I took note of his observations and ensured my work was as he requested, resulting in positive feedback of my company to the main contractor.

Frustrated and unwilling to continue at a loss, I sent a letter to the company requesting payment of my applications in full or I would withdraw from both projects.

The company summoned me to a meeting with senior management.

I presented my case, and as the projects manager arrived late, the contracts manager turned to him and decisively said “pay him as per his applications”.

I continued working with this main contractor for many years afterwards.

It was a turning point, affirming the importance of persistence and self-advocacy.

Years later, a life changing accident plunged me into a dark place.

But through my wife’s unwavering support, I persevered.

I’ve learned that resilience and hope are vital, even in the toughest times.

Edgar A Guest’s poem ‘Don’t Quit’, became my mantra, offering strength to push forward.

No matter the obstacles, remember that challenges are temporary.

Reach out, stand firm, and never give up, because brighter days are always within reach.

THE DIFFICULTY TODAYS APPRENTICES FACE

In 1980, I embarked on a three-year carpentry and joinery apprenticeship under the guidance of a master craftsman.

My mentor not only taught me how to sharpen and use my tools, but also instilled the essential principles of the trade.

From creating tight joints, taking the arris off finished timberwork, punching nails below the surface, avoiding crowning of timber, to ensuring screw slots aligned vertically to allow the paint to run out, every lesson was a step toward mastering the craft.

During my apprenticeship, I learned first, second and third fixes, truss roofing and basic formwork.

While I wasn’t fully competent by the end, I had a strong foundation to build on, thanks to having the same mentor throughout.

Crucially, he wasn’t on price work, so he dedicated the time to ensure I achieved high standards.

Despite the challenges of job security, particularly during the recession in my final year, I was fortunate to keep my job.

Today, apprentices face a different landscape.

Modern NVQs can be achieved in just two years, and the prevalence of self-employed tradespeople often means mentors are too focused on deadlines to offer thorough training.

As with the past, job security remains scarce, adding further pressure to the apprenticeship journey.

My advice to aspiring carpenters is to focus on mastering the basics.

Strive for high standards, maintain a clean and safe workspace, and approach each task with care.

With time, speed and expertise will naturally follow.

The foundation of quality work laid during your apprenticeship will set you apart and make you highly sought after as your career progresses.

There’s great satisfaction in seeing your skilled work admired by others, a testament to the craftmanship achieved with your hands. And with that quality comes financial rewards.

‘ITS NOTHING PERSONAL MARK, ITS JUST BUSINESS’.

The construction Industry is a challenging arena, fraught with financial disputes and underpayment issues.

One moment vividly etched in my memory was when I confronted a quantity surveyor about my joinery company’s underpaid monthly application.

Their dismissive response, ‘it’s nothing personal Mark, it’s just business’, left me stunned.

It is personal, it’s my money earned through hard work, that feeds my family.

My question to them, ‘How would you feel if you were underpaid?’, was met with silence.

Underpayment isn’t just a numbers game, it’s a pressing issue with real-life consequences.

Many quantity surveyors lack a true connection with suppliers, often overlooking the ripple effect underpayment creates.

It strains businesses’, disrupts livelihoods, and undermines trust.

Even more troubling is the recurring phenomenon of construction company directors evading accountability after their businesses fail.

These failures leave behind unpaid suppliers, incomplete projects, and abandoned sites that tarnish neighbourhoods and become hotspots for antisocial behaviour.

Yet, somehow, these directors often resurface in new ventures, free from the financial ruin they’ve left behind.

There must be accountability in this industry.

Suppliers and communities are not disposable resources to be exploited and abandoned.

They are assets vital to the fabric of construction and society.

Until the industry embraces fairness and enforces stricter regulations, the cycle of financial harm and disregard for people’s livelihoods will persist.

It’s time for change, because it is personal.

ADDRESSING CHALLENGES IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY.

The construction industry faces unique challenges that contribute to high dropout rates, job insecurity and a troubling mental health crisis among workers.

Statistics reveal a 47% of apprentices in construction failed to complete their programmes in 2023 to 2024 largely due to layoffs or redundancies.

This instability stems from the nature of construction work, where many tradespeople are self-employed and vulnerable to disruptions caused by weather, design issues, material delays or dependency on other trades.

A major issue is the lack of consistent and timely payment.

Workers often face delays, unexpected payment shortfalls, and even theft of tools, all of which exacerbate financial stress.

The cyclical nature of the industry, which is one of the first to feel the effects of recession and the last to recover, only worsens the situation.

For management unpredictable variables like weather and design delays create additional pressure to deliver projects on time and within budget.

This relentless environment, coupled with inadequate job security and unrealistic deadlines, has contributed to the construction industry having one of the highest suicide rates.

It is clear that systemic change is required to improve conditions for workers.

Offering secure employment contracts, ensuring prompt and fair payment, and allowing realistic project timelines would significantly enhance job satisfaction and mental health.

By addressing these foundational issues, the construction industry can create a more sustainable and supportive environment for its workers, fostering both personal and professional growth.

If these changes are not made, the industry risks continuing its cycle of high dropout rates, mental health struggles and overall inefficiency.

I have over 40 years of experience in the construction industry, having worked as a joiner, owned a carpentry and joinery contracting company and served as a freelance site manager.

THE IMPORTANCE OF EXPERIENCE

At the age of 24, just a few years into running my own Joinery and Carpentry business, I had the unique opportunity to be involved in the construction of the Grand Canyon ride at Alton towers, (renamed Congo River Rapids) being constructed by Sir Robert McAlpine.

(I managed to secure the opportunity from sub-contracting to a local firm the previous year, who were involved with the new front entrance at Alton Towers being constructed by Sir Robert McAlpine. The Contracts manager at Sir Robert McAlpine had been impressed with my attitude, speed and joinery skills and asked me for my contact details. Always worth giving a 100%, you never know what doors might open)

My company was tasked with shuttering about a third of the water flume through a rock area that had to be blasted to make way for the flume.

I assembled a team of seven shuttering joiners all of whom were older and far more competent than me.

The original design called for shuttering on both sides of the flume wall, however, in this section it was decided to forego shuttering of the outer face and instead use the blasted rock face as formwork for this part of the wall.

One of the challenges faced was the creation of expansion joints every sixteen metres, which required a water bar and dowels, as it was crucial that the flume did not leak.

These joints had to be inspected and signed off by the engineer before any concrete could be poured.

As the project neared completion, one of my joiners asked the engineer about the purpose and function of the expansion joint.

The engineer explained it, but the joiner, noticing an issue, pointed out that the wall had been poured all the way back to the rock face, which restricted the expansion joint from functioning as designed.

The engineer’s face dropped upon realising the error.

This moment highlighted the importance of collaboration and constant communication on site.

It also reinforced the importance of experience, no matter who it comes from, is invaluable in ensuring projects stay on track and function as intended.

I have over 40 years of experience in the construction industry, having worked as a joiner, owned a carpentry and joinery contracting company and served as a freelance site manager.

NEVER ASSUME, ALWAYS CHECK

Several years ago, a significant safety incident occurred during the construction of a timber frame extension for a hotel chain.

The event involved a Mantis crane operated by a joiner who had been trained to use it, tasked with lifting the various timber kit parts for the project.

At one point the scaffolder (who was also trained to use the Mantis crane) asked the joiner if he could use the crane to lift some scaffolding.

The joiner handed the remote controls over to the scaffolder, the crane hook block was elevated well above the surrounding building.

The Scaffolder completed the lifting tasks and then handed the controls back to the joiner, however the crane hook block was in a lowered position just above the ground.

Unaware that the crane hook block was in this position, the joiner proceeded to slew the crane 180 degrees assuming that the crane hook block was in the same elevated position as when he had handed the controls to the scaffolder.

As a result, the crane hook block dragged across the car park damaging several parked cars, before it continued along the side of the hotel, tearing through the roof and onto the road, where the hook block entangled itself around a lamp post.

Fortunately, no one was injured in this incident, but it highlights the risks associated with assuming, and not checking.

On returning to work after the Christmas holiday be extra vigilant.

Review your work area, identify the hazards, and ensure control measures are in place to either eliminate or reduce the risk of those hazards occurring.

HOW DO YOU PROVE COMPETENCY?

Passing a driving test and receiving a certificate doesn’t necessarily mean you are a competent driver.

Insurance companies understand this, which is why newly qualified drivers often face high premiums.

Even if a black box tracks their driving to ensure safety, it only verifies that they’re not driving recklessly, it doesn’t prove that they are skilled.

That raises the question, does achieving a qualification like an NVQ truly make someone competent in their profession?

In construction simply passing an exam or obtaining a qualification such as an NVQ doesn’t guarantee competency.

Like a newly licensed driver, a qualified worker may still lack experience to handle the complexities of their job.

In my own career as a carpenter and joiner, during my three-year apprenticeship, I only worked on a few projects gaining limited exposure to the full scope of my trade.

It wasn’t until ten years later, after working on diverse projects and learning from more experienced tradespeople that I felt competent, but I still had a lot more to learn.

How long does it take therefore to gain competency in construction?

In my opinion at least ten years of experience is necessary to reach a reasonable level of skill.

When I served my apprenticeship, I shadowed the tradesperson that taught me my profession for three years, a small family run building company, which had around twenty directly employed tradespeople.

However, with modern apprenticeships and subcontractors on price work, is the knowledge of these older tradespeople being passed on?

While modern apprenticeships are still valuable, the focus on qualifications can sometimes overlook the importance of mentorship and hands on learning.

In the past site supervisors and managers often came from a trades background, and rose through the ranks gaining invaluable experience along the way.

With the younger generation of tradespeople lacking this mentorship, the future of construction could face challenges.

As this older generation leaves the industry through retirement or through exclusion with the insistence of NVQ qualifications for example, if this knowledge has not been passed on, surely the concern with future construction is not only the lack of tradespeople, but the knowledge to build correctly, foresee problems and have the competency to overcome those issues.

A CONVERSATION WITH A CONSTRUCTION MANAGING DIRECTOR

I recently had a conversation with a Managing Director of a construction company who expressed frustration with people who point out hazards in photographs posted on social media by construction firms.

I found this surprising, as I believe this kind of scrutiny could be valuable for improving safety practices.

Instead of viewing these observations as poor publicity, companies could use them as an opportunity to learn of potential risks and reinforce their commitment to health and safety.

It’s important to remember that when health and safety officers conduct site audits and identify hazards, they aren’t criticising the team, but instead, helping to prevent future hazards.

Adopting a similar mindset toward social media feedback would benefit the industry.

Viewing these comments as constructive rather than negative could encourage a culture of continuous improvement.

Moreover, it’s common to use numerous health and safety issues in television programmes about self-builds and home renovations.

These shows often highlight serious hazards like improper scaffold, unprotected edges, dust or inadequate safety gear, which could easily lead to accidents or long-term health issues.

If construction companies and site managers adopted a more open-minded approach to feedback, whether from professionals or the public, then they can stay ahead of potential risks and create safer working environments.

Ultimately, safety should always be the priority.

Rather than ignoring or rejecting criticism, embracing it can lead to a stronger safety culture, better practices, and fewer incidents on construction sites.

This is the kind of mindset that can ultimately protect workers and improve a company’s reputation, both online and offline.

ARE YOUR SUPERVISORS REVIEWING THEIR WORK AREA?

Accidents at work can have severe consequences, not only for the injured person but also for the company.

When these accidents occur, the question often arises, who is to blame?

In many cases supervisors play a crucial role in ensuring workplace safety, and failure to adhere to their responsibilities can lead to significant legal repercussions under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. (HSWA)

HSWA emphasises the importance of proactive safety measures in the workplace.

Supervisors must recognise their crucial role in fostering a safe environment and take their responsibilities seriously. By doing so, they not only protect their team but also safeguard the company from potential legal issues and financial loss.

Part of the supervisor’s role is to regularly review their work area, identify the hazards and ensure control measures are put in place.

So, if an accident occurs on your site, how do you show to the HSE that the supervisor has been reviewing their work area?

When I had my life-changing accident, the supervisor failed to identify that the ground that the ladders were sitting on was covered in Lichen (which is incredibly slippy when wet).

The ladders were wedging the scaffold gate in a permanently open position and were not as TG20.

The ladders were not secured to the scaffold which was part of the prestart checks.

I failed to notice all the above along with the other three roofing operatives using the same access.

This is why it is crucial that Site supervisors are competent and regularly review their work area, identify hazards, and ensure control measures are in place, and communicate this information to the operatives that they are supervising.

How did the company who I had the accident with try to limit their liability? They removed their directly employed site supervisor as the person in control of the works, and passed all the blame onto the subcontract roofers, and amended the paperwork to suit before the HSE got there.

If the supervisor had carried out his role correctly, my life changing accident would not have happened. If my free to use app had been used, not only would the supervisor have noticed all the hazards with no control measures, but the supervisor would then have passed the information on to me and the other three roofing operatives, so that we would learn about those hazards and the control measures that should be in place.

By no means does this exonerate me for being partly responsible for my accident, but I did not know about Lichen or TG20, both of which I now know, but the cost for this lesson a life changing accident and untold trauma to my family.

Everyone needs to regularly review their work area, identify hazards and ensure control measures are in place. We all have a duty for our own and our work colleagues safety.

The ripple effect of the trauma that an accident at work can have on the injured persons family and loved ones is far reaching and unforgiving.

DOES THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY REALLY CARE ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH, OR IS IT JUST ANOTHER BOX TICKING EXERCISE?

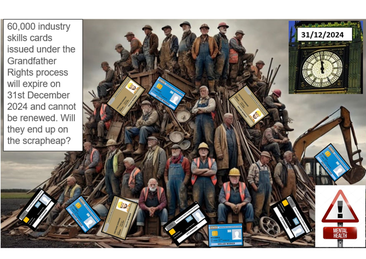

The scrapping of the CSCS grandfather rights cards at the end of the year, has left many experienced workers in the construction industry facing uncertainty, not only affecting their livelihood but also their mental health.

For years, these workers have built careers based on experience, but now face themselves at risk of being discarded with little regard for the toll it takes on their well-being.

The decision to remove these rights fails to acknowledge the human cost and how it can affect the mental state of those who have devoted decades to the trade.

Mental health in the workplace has become a key issue in recent years, but too often, it feels like little more than a box ticking exercise.

While there may be surface level efforts to address stress and well-being, the reality is that workers are under immense pressure to meet targets set by the company’s shareholders.

From the MD down to the site manager, the pressure is relentless.

The site manager, in particular, bears the brunt of the stress, trying to meet impossible deadlines while ensuring the safety and quality of the work.

If a site manager were to speak up about unrealistic targets, it is unlikely the MD would simply say “do your best”.

In a capitalistic society driven by profit, it’s about delivery, not people.

Workers, whether managers or tradespeople, are often driven by financial incentives or the fear of being replaced if they don’t perform.

The corporate focus on profit leaves little room for genuine concern about the well-being of employees.

Ultimately, the scrapping of grandfather rights and the relentless drive for profit in the construction industry highlights a fundamental issue.

Workers are seen as resources to be used, not as individuals with mental health needs and personal lives outside of work.

In this system their well-being often takes a backseat to the bottom line.

If there was genuine concern for mental health in the construction industry, then those affected by the removal of grandfather rights CSCS cards at the end of the year should have been reassessed and granted the relevant NVQ free of charge.

Instead, workers are left with the added stress of applying for grants, if they are even able to, whilst many others have no such option and have the stress of trying to find the money to pay for an NVQ.

I also wonder whether the construction industry can afford to lose such a significant skill base.

Will companies be forced to abandon the CSCS card system as they struggle to meet deadlines due to a shortage of skilled labour and competent managers, ultimately turning potential profits into losses?

IS IT WORTH IT?

After my life changing accident, I found myself in a dark place - emotionally, mentally and physically.

It was a place that wasn’t good for me or my family.

I was so close to losing everything that I had worked so hard for.

The stress of running my own business, worrying about getting paid, managing labour, securing enough work and even the weather forecast, all piled up, and then came the question “Is it worth it?”

I recently had a conversation with a site manager. He said, “You can only pee in one pot and sit in one seat”.

At first it seemed a strange analogy, but the more I thought about it the more it made sense.

Why do we strive for more pots, more seats, better quality pots, better quality seats?

When is enough really enough?

It made me reflect on my own journey.

Having served my joinery apprenticeship, then working for various construction companies increasing my knowledge, I found myself as a young joiner working for a shopfitting company.

I remember the foreman joiner who worked for the shopfitting company was always working hard, pushing himself to his limits.

I left the company after 6 months and set up my own joinery and carpentry business.

Some years later, a builder who I was subcontracting to was asked by some of his wealthy friends to convert a disused building into a laser tag arena and café.

It was beyond the builder’s remit, but he brought me to the meeting with his wealthy friends and I put a package together, which included the shopfitting company that I used to work for.

When I met the foreman joiner for the shopfitting company, he had been promoted to the contracts manager and we caught up on old times.

The project went well, and my company picked up another project from the shopfitting company.

About five years later, I saw a picture in the local paper of the contracts manager, he looked as though he had aged considerably.

He had started his own company, which had grown exponentially, but with this success had come a lot of pressure, especially with cash flow and this had clearly taken its toll on him.

In the end I believe the company became insolvent.

It was a similar pattern with the builder, who had become obsessed with retiring when he was forty, constantly taking on more and more projects to fund his future retirement.

He never managed to keep hold of his retirement fund, lost a lot of his assets and it destroyed his marriage.

But here’s the thing, you only have one life.

No amount of wealth or possessions can replace your health or peace of mind.

We get so caught up in striving for more that we forget the importance of mental health.

Take care of yourself.

Take care of your mental health.

Possessions and achievements may come and go but you are irreplaceable.

If you are struggling with your mental health, please reach out, there are plenty of organisations that can offer support.

IS THE REMOVAL OF THE CSCS GRANDFATHER RIGHTS GOING TO REDUCE BUILD QUALITY ?

On Wednesday, I took my vehicle in for a service, and something unexpected happened that really made me think.

When I dropped it off, the vehicle was far from clean, so I could easily see areas that had been worked on. When I returned to collect it, however, it looked like nothing had been touched.

I challenged the garage, and after some back and forth, they agreed there would be no charge for the service.

Had my vehicle been clean to begin with, I likely would have never suspected a thing. It was only because I knew where work should have been done, that I could challenge what I saw, or more accurately, what I didn’t see.

This got me thinking about my role as a freelance construction site manager. In many ways, it mirrors the situation I faced at the garage.

As a site manager, I need to have a deep understanding of construction processes to ensure work is done to the highest standards.

This includes checking things that might be covered up or hidden from view, just as I would check the work done on my vehicle, even if the visible signs aren’t immediately apparent.

Experience is critical in this regard. Having been in the industry for over forty-five years, I’ve learned to spot issues that might otherwise go unnoticed, but this isn’t always the case for everyone in the field.

With the upcoming removal of grandfather rights CSCS cards at the end of the year, there is growing concern about the implications for the quality of work on construction sites.

While the NVQ system is in place to tests operatives’ knowledge, how effective is it in ensuring the level of construction knowledge needed to maintain high-quality standards on site?

In many cases operatives can pass an NVQ without truly understanding the full scope of their craft, especially in a fast-paced construction environment that focuses on completion rather than quality.

The removal of grandfather rights may level the playing field in terms of qualifications, but does it prove competency?

Will it lead to more work being covered up and passed off as finished without true attention to detail?

Without proper depth of knowledge, operatives might be incentivised to board over faults, hide mistakes or simply not have the skills to identify issues in the first place.

At the end of the day, it’s our responsibility, as construction professionals, to ensure that work is done properly, even if it is behind the scenes or out of sight.

The same way I challenged the garage over their service, we need to be vigilant in ensuring quality work on construction sites, not just for the sake of compliance, but for safety and durability of the structures we build.

THE RIPPLE EFFECT OF WORKPLACE ACCIDENTS.

Workplace accidents often have immediate and visible consequences, but their effects extend far beyond the injured individual. The ripple effect can impact family members, colleagues and even the broader organisational culture. I want to show the interconnected consequences, including mental health challenges for those close to the injured, deceit surrounding accountability, and the implications of funding issues in medical care.

When I suffered my workplace injury, the emotional burden was profound. Family members experienced anxiety, fear and helplessness. The sudden change in my capabilities as head of the family led to feelings of grief and loss, and my wife struggled with the increased responsibilities and stress. This emotional upheaval created long-lasting mental health issues, not just for me, but for my family.

Colleagues may feel the ripple effect in the workplace accident. Witnessing an injury can cause trauma. Employees may become fearful of their safety, which can alter workplace dynamics and reduce teamwork. Additionally, the organisation might face increased scrutiny, prompting a culture of distrust if employees feel that management is not transparent about the circumstances of the accident.

In the aftermath of an accident, the quest for accountability of an accident in my case led to deceit and cover-ups. Those responsible for maintaining safety protocols deflected blame to protect themselves. This sort of deceit can erode trust among employees, leading to a culture where safety is compromised. When accountability is sidestepped, it fosters resentment and a sense of injustice further impacting workplace morale.

The quality of medical care following a workplace accident can be significantly affected by funding issues, as I experienced, probably sent home to die. Underfunded medical facilities may prioritise cost-cutting over patient care, resulting in rushed diagnosis and inadequate treatment. This can exacerbate the physical and emotional challenges faced by the injured worker and their family. Poor decision-making by healthcare professionals, driven by financial constraints, can lead to long-term consequences, both physically and mentally.

The ripple effect of workplace accidents is complex and far reaching. From the emotional struggles of family and friends to the implications of deceit and inadequate medical care, the consequences extend well beyond the injured individual as I have experienced and witnessed.

Addressing these issues requires a holistic approach that prioritises transparency, mental health support and adequate funding of medical care, without this, the feeling of worthlessness by the injured person can only make them head in one direction, potentially causing even more trauma to those around the injured person.

From my own personal experience, the people most affected by my accident, were not even at the scene of the accident, my family.